A common frustration of working in the Dangerous Goods supply chain is “keeping up with constantly changing regulations.” Why do the rules change so often?

One reason regulations change? It’s to prevent incidents like the devastating 2012 explosion aboard the container ship MSC Flaminia, in which three crew members were killed. Earlier this month, the U.S. District Court for the Southern District of New York reached a decision assigning fault in that incident to the manufacturer and freight forwarder of a shipment of divinylbenzene (UN 1993).

July 14, 2012 (The Maritime Executive, 9-14-18)

The 39th Amendment to the IMDG Code—the required manual for anyone shipping Dangerous Goods by vessel—contains a new, six-page redraft of the rules for transporting polymerizing substances. These newly clarified regulations may have prevented the Flaminia disaster had they been in effect six years ago.

Why polymerizing substances need special regulations

Polymerization is a process where relatively small molecules combine chemically to produce a larger, chainlike molecule. These chemicals—which also include acrylic acid (UN 2218), styrene (UN 2055) and ethyl acrylate (UN 1917)—are essential for the manufacture of many common plastics.

They also pose particular perils for maritime shippers, as described at the recent Dangerous Goods Symposium by maritime Dangerous Goods veteran Richard Masters:

“Polymerizing substances can be innocuous until they reach certain temperatures, and then they misbehave. Their molecules respond to a rise in temperature with a runaway self-reaction leading to violent physical expansion and emission of heat and gas.

“In winter, when ambient temperatures are low, with careful planning and monitored deck stow it is possible to move these substances by sea without mechanical temperature control. However, it must always be remembered that some parts of a ship below deck are constantly heated by the ship’s machinery, and careful attention to stowage is essential.

“In summer, higher ambient temperatures narrow the margin to the maximum safe carriage temperature, making it imperative to fully understand and comply with the new 2019 IMDG Code rules for mechanical temperature control, deck stowage and monitoring.

“Once the reaction starts, you can’t reverse it. The material sublimes into hot gas under immense pressure that can rupture the tank, and with compressed gas in vast quantities, the smallest spark can ignite it. It’s an explosion waiting to happen.”

How the new IMDG regulations affect shipments of polymerizing substances

The previous edition of the IMDG Code “tried to clarify IMDG procedures for polymerizing substances—and failed,” says Masters. “It added polymerizing substances as a hazard, but didn’t explain specifically enough what shippers had to do to control the hazard.

“There is no absolute control over temperature exposure unless cargo is carried in a mechanically controlled environment. Section 7.3.7 has been rewritten to clarify the process for temperature control.”

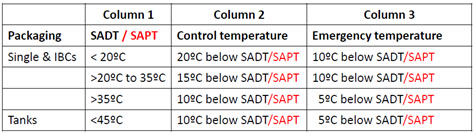

This clarification includes a new table for determination of control temperatures for polymerizing substances, and requires the shipper and carrier to make judgments on variable factors, including:

- The seasonal ambient temperature

- The length and route of the voyage

- The stowage position on the ship

“The 39th amendment makes it very specific. You have to say this is a polymerizing substance, either stabilized with chemical inhibitors or under temperature control, and explain to the carrier that the ambient temperature must not exceed a certain point.”

Preventing another maritime disaster

On July 14, 2012, with the Flaminia underway from New Orleans to Antwerp, smoke appeared from a cargo hold. When a seven-man team prepared to fight what they thought was a fire, a spark ignited the gases escaping from the ruptured tanks of divinylbenzene in the hold.

The tanks had been stored in the New Orleans sun for 10 days before being loaded aboard the Flaminia, then stowed in the vessel near the ship’s heated bunker fuel tanks. Experts testified that these conditions were causal factors in the chemical reaction and the explosion, and the court found that only the cargo manufacturer and freight forwarder were at fault.

Will the updated section 7.3.7 help ocean carriers better prepare for the risks of carrying polymerizing chemicals? Masters believes it will, and hopes such regulations will reduce the number of Dangerous Goods incidents at sea.

“There’s a major fire at sea every 60 days. The explosion and fire on the Maersk Honam in March this year looks to be the largest general average insurance claim in maritime history. Maritime Dangerous Goods come from the four corners of the globe, and with millions of containers each year it’s difficult to check if each is packed properly.

“Society is aware when an aircraft crashes, but when there’s a ship fire no one knows about it. It’s off everyone’s radar, but money is lost and people die.”

Labelmaster is a full-service provider of goods and services for hazardous materials and Dangerous Goods professionals, shippers, transport operators and EH&S providers. See our full line of solutions at labelmaster.com.